The case studies presented in this report demonstrate that making major strategic change in U.S. foreign policy involves not just the White House but also the government bureaucracy, Congress, the wider expert community, the public, and foreign actors. Proponents of change need to account for all these actors to some degree in order to be successful.

This chapter draws conclusions from the case studies and adds insights from other cases and relevant scholarly literature. It identifies practical lessons for future U.S. leaders and policymakers who seek to bring about major change in foreign policy.

The chapter begins by explaining why crisis facilitates change and by exploring the implications of this finding. It then examines why various parts of the government bureaucracy tend to resist major changes, as they did in nearly every case. The chapter proposes three ways to encourage the bureaucracy to adopt change more willingly. Next, the chapter explains why Congress matters for strategic change, identifying the political conditions under which it is likely to support rather than resist change. The following sections examine the role of public opinion and the psychology of change, which suggest ways to convince the many stakeholders involved in foreign policy that change is needed. The chapter concludes by considering the limits of presidential power in making major changes in America’s role in the world, arguing that an incremental and reformist approach is likely to be most effective.

Crisis Facilitates Change

The case studies show that crisis is a great driver and facilitator of change and that foreign policy leaders should have an idea of how they might use a crisis to open or foreclose opportunities to shift strategy. The case of 9/11 makes the importance of crises unmistakably clear, but international crises spurred change in the NSC-68 and Vietnam War cases as well. There is truth in the adage “Never let a good crisis go to waste.” Crises generate policy plasticity, opening the door to strategic change. Absent a crisis, a president seeking significant changes in foreign policy faces a much harder task.

Consider the impact of the outbreak of the Korean War on U.S. Cold War strategy. The hawkish global approach that Nitze developed in NSC-68 initially faced opposition inside and outside the government. The plan was basically shelved in the spring of 1950, and it gained new life only when the Korean War erupted in June. North Korea’s invasion of South Korea seemed to support NSC-68’s central claim that the United States could not afford to focus solely on competition with the Soviet Union in Europe. The outbreak of the war also created a sense of urgency that NSC-68’s advocates used to turn their strategy into a reality. As a result, the United States adopted a more geographically expansive and military-centered conception of how to wage the Cold War.

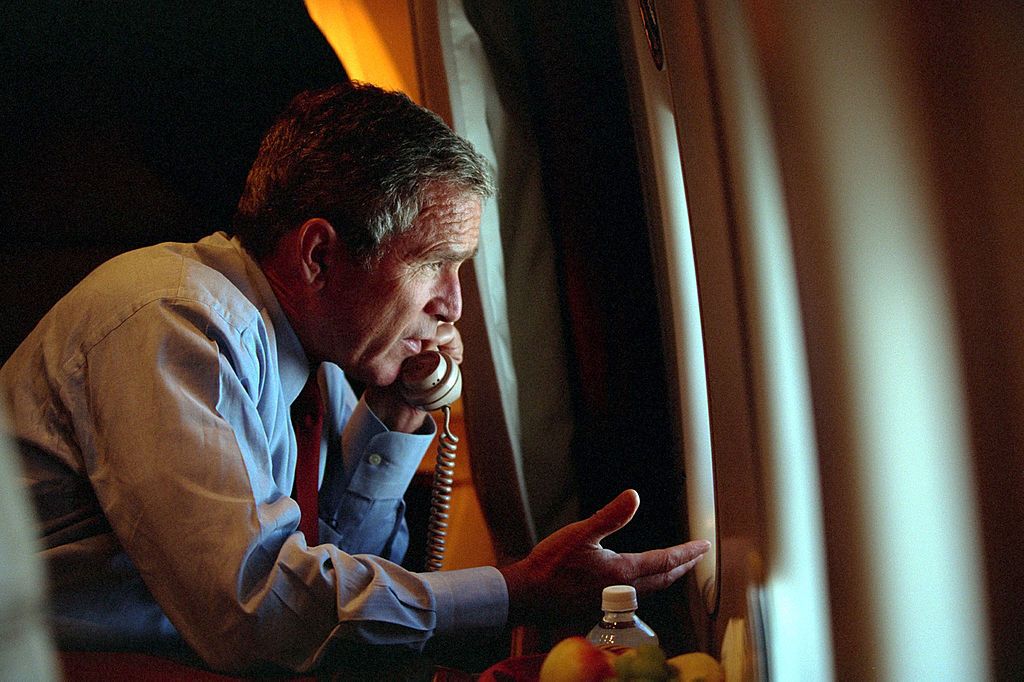

The 9/11 attacks provide an even more clear-cut case of how a foreign policy crisis fosters major change. The terrorist attacks created so strong a national desire to punish al-Qaeda and to prevent another assault on American soil as to give the Bush administration as close to a free hand in foreign policy as any presidency since the Second World War. The White House used the crisis not just to put a higher priority on counterterrorism but also to increase defense spending and implement a neoconservative grand strategy aimed at building democracy in the Middle East through military force.

Conversely, Carter’s failed attempt to withdraw U.S. forces from South Korea illustrates the difficulty of achieving significant change without a crisis to motivate and galvanize support for it. Carter came into office on the heels of economic and foreign policy crises: the 1973 inflation spike and the Vietnam War. The latter was one reason he wanted to reduce the U.S. military posture in Asia by withdrawing forces from South Korea. By the time he took office, however, these problems had lost intensity. Support for withdrawal from South Korea dissipated over time, and Carter was eventually forced to shelve the idea.

Crisis is not always necessary for major change. The Biden administration withdrew from Afghanistan in 2021 in the absence of a foreign policy crisis. It decided to withdraw U.S. forces in the first year of the administration, during a honeymoon period when the president still enjoyed strong support from his own party and control of Congress. The policy had also been pursued by Trump, making it more difficult for Republicans in Congress to criticize the withdrawal harshly. By 2021, moreover, evidence that the United States was not achieving its stated objectives in Afghanistan had piled up over the years, weakening resistance to change and making withdrawal popular among a large majority of the American public.

Why do crises facilitate change? One reason is that they tend to generate an emotional impetus for action, making people more likely to rethink their fundamental assumptions and goals. In a time of crisis, the public, Congress, and the government bureaucracy yearn for a response. Pressure for action is not always a good thing, because sometimes the best policy is to avoid taking action in the first place—in other words, to do nothing—but if the White House is aiming for a major change, a crisis generates a permissive atmosphere for change to gain traction.

Crises can also overwhelm existing beliefs with disconfirming information. In normal times, people tend to interpret facts according to existing mental frameworks rather than to revise the frameworks themselves. But a crisis can cause people to rethink assumptions if an existing framework has proven to be inadequate for understanding the world and generated harmful consequences. In addition, crises generate a sense of urgency, which can generate the momentum needed to overcome inertia. Experts on change in businesses, for example, have pointed out that a sense of urgency can be essential to large-scale change because it helps generate collective action.

A crisis does not determine a particular policy response, however, even if it creates the emotional and psychological basis for change. Even shocks like 9/11 or the Korean War were interpreted in different ways and could have produced different policy outcomes. Policy alternatives are always available. For example, in the case of 9/11, the choices to pursue the Global War on Terror and invade Iraq were shaped by American strategic culture, preexisting threat perceptions of Iraq, and other factors. During and after a crisis, policymakers will disagree about the causes of the crisis, the potential responses to it, and the relevant high-order goals and interests at stake. Some may see their own interests advanced or set back by the alternatives on offer. Moreover, when a crisis has triggered strategic change, that change has often been conceived and proposed prior to the crisis. Rather than emerging from the objective properties of a crisis itself, the “solution”—as in the cases of NSC-68 and the invasion of Iraq—already existed as an idea and then gained acceptance out of a belief that the crisis would have been prevented or been easier to address had the strategic change been adopted earlier.

Still, there was certainly a relationship between foreign policy crises and the strategic changes they have produced. The Korean War helped to strengthen the case for the globe-spanning recommendations of NSC-68 because it was a crisis in Asia, not Europe. The 9/11 attacks resulted in changes aimed at addressing the new threat from terrorist organizations and actors in the Middle East. Any White House would have adopted a greater emphasis on terrorism, even though not all of the policies adopted by the Bush administration were made inevitable by the 9/11 attacks themselves.

Absent major external shocks, strategic change remains very difficult in U.S. foreign policy, where policies are often highly institutionalized and supported by many interests and groups in Congress, the different government bureaucracies, the expert community, and the broader public.

Nor will any foreign policy crisis be enough to generate major change. Absent major external shocks, strategic change remains very difficult in U.S. foreign policy, where policies are often highly institutionalized and supported by many interests and groups in Congress, the different government bureaucracies, the expert community, and the broader public. Moreover, crises may facilitate certain types of change but not others. In most cases since the Second World War, crises generally triggered a strong impulse to “do something,” leading to an expansion of U.S. programs and activities and causing a policy of restraint to receive little hearing. Crises—whether the Korean War, the end of the Cold War, or 9/11—are not normally conducive to disciplined foreign policy.

Why Bureaucracies Resist Change

Most of the cases studies reveal the importance of bureaucratic resistance to change. Sometimes, as when the military and civilian bureaucracies mounted a campaign against Carter’s attempted drawdown in South Korea, resistance succeeded. In other cases, resistance was thwarted, whether by the maneuvers of a small group within the bureaucracy, by secrecy in the White House, or by congressional and public pressure.

The different government bureaucracies are essential instruments through which power must flow when presidents employ political, diplomatic, intelligence, and other forms of power. Presidents cannot overlook or circumvent them when seeking to introduce foreign policy change. There is no diplomacy without the State Department and no military action without the Pentagon. Strong bureaucracies make the United States more powerful and more capable—but they are difficult to change and make change difficult.

Foreign policy bureaucracies are highly complex organizations that enjoy a great degree of independence and maintain deep relationships with Congress and expert communities outside the government. They also have strong internal values, cultures, and perspectives on foreign policy. It is not surprising that they routinely pursue their own interests that transcend administrations and that they resist presidential orders to do things they have not been organized and programmed to do.

Obama, for example, entered the White House promising to close the U.S. detention facility at Guantanamo Bay, but he met staunch pushback from parts of the national security bureaucracy that successfully thwarted his plan. Resistance varied across the government, but Obama’s failure is evidence of how bureaucracies are conditioned to preserve the existing way of doing things—in this case to preserve the policy that emerged after the 9/11 attacks. The Trump administration also faced a great deal of bureaucratic pushback on foreign policy. Trump tended to portray this obstacle as stemming from a nefarious “deep state” and a civil service dominated by political adversaries. Parochial bureaucratic factors were probably more important.

One reason bureaucracies resist change is fear that it will threaten their interests. The State and Defense Departments tend to resist change when they expect it will impose new requirements on them, constrain their budgets, damage their institutional influence within national security decisionmaking, or alter their basic mission. Bureaucrats may also resist change if they worry it will be costly and cumbersome to implement. Major foreign policy change inevitably requires new bureaucratic procedures and routines. These detract from existing ones that have advocates within the bureaucracy, all of whom will resist change. Organizational culture is another source of resistance: bureaucracies have identities, and civil servants hold beliefs about their organization, its role, and why they do what they do. This gives them a sense of mission that drives their work. If the White House tries to implement a policy running counter to the organizational culture that animates a bureaucracy, resistance is almost certain.

Major foreign policy change inevitably requires new bureaucratic procedures and routines.

Moreover, even when tasked to implement a strategy whose goals the bureaucracy largely accepts, officials still have a strong bias in favor of using existing capabilities to do so, even if these capabilities are not well suited to the task. Officials will make the case for the appropriateness of their organization’s existing capabilities because they believe this is their job. They are unlikely to admit, or sometimes even recognize, that new policy objectives require new ways and means. For example, the United States’ tendency to turn to the military instrument is in part a reflection of the size of its military capabilities and of the Pentagon relative to other foreign policy actors.

The tendency of bureaucracies to cling to existing procedures and tools to implement new policies—even when inappropriate—is part of a larger principal-agent problem that any White House faces in dealing with agencies such as the State Department, the Pentagon, and the intelligence community. The problem is that the president must delegate implementation to the bureaucracy, which has greater knowledge of and control over outcomes than the president. Because it can be very hard for the principal to monitor implementation, the agent ends up with wide latitude to shape the policy. Once the White House has decided to make a particular change in policy, it can prod, pressure, monitor, and cajole the different bureaucracies to do what it wants, but it cannot be totally sure of how much they will follow through. Part of the problem arises from the fact that the expertise needed to implement a change in foreign policy can often be found only within the bureaucracy. Presidents may understand the broad outlines of the foreign policy they seek but almost certainly lack the expertise to understand how to implement it. Paradoxically, the more the White House draws on the expertise of the organizations required for implementation, such as the Defense Department, the more it will import the culture and aims of that organization into the policy, and the less likely change will occur.

Bureaucracies have several means at their disposal to push back against change they dislike. For one, officials may directly defy orders. This stark approach, however, comes with many risks and is not always effective. For example, the many resignations from the State Department during the Trump administration had little effect on White House policy. They may even have been welcomed by an administration that wanted to gut the bureaucracy. Alternatively, simply not acting on orders or acting very slowly— “slow rolling”—is a less risky and more effective strategy. For example, the Defense Department repeatedly slow-rolled Trump’s orders to withdraw U.S. forces from Syria, where they remained when he left office. The department, which had spent blood and treasure fighting there for years, saw these orders as precipitous and capricious, and so military leaders leveraged their knowledge of operational realities to delay and obstruct what the president wanted.

Bureaucracies can also leak negative information to the press, work with allies in Congress to undermine policy objectives, encourage expert networks outside government to attack the White House, and appeal to special interests to fight against change. In the current polarized and sensationalist political environment, there will almost always be an appetite for leaks in the media and a willing and powerful set of interests ready to take advantage to hinder new policy or just score partisan political points.

Bureaucratic resistance to change has led to some experts to warn about the emergence of a “deep state” that thwarts the objectives of democratically elected presidents. This charge can be misleading because the government bureaucracy is unlikely ever to act as a united front in opposition to or support of White House objectives. Different agencies stand to lose or gain from policy change in different ways, so resistance will vary accordingly. It will vary even within some larger bureaucracies, such as the Department of Defense, or across the multiple agencies that comprise the U.S. intelligence community. A key element of successful management of the bureaucracy will therefore always be the advance identification of where these areas of resistance or advocacy are likely to lie, so that the resistance can be neutralized and the advocates empowered.

Winning Bureaucracies Over to Change

When bureaucratic resistance to policy change is soundly rooted in legal statutes, there is little the White House can do to overcome it. Many statutes, though, leave room for interpretation by attorneys in the different bureaucracies themselves or in the Office of Legal Counsel at the Department of Justice. In theory, replacing those who make interpretations contradicting a proposed change would be one way to overcome resistance. But such a gambit would be ethically questionable and likely to face legal challenges. Fortunately, there are other ways to make bureaucracies go along with change.

The first and most important way is through political appointments. All administrations appoint political allies to key positions in the different government bureaucracies, and there are several thousand such appointees in the executive branch overall. They can change the agencies to make them comply better with the president’s agenda rather than their own. Political appointees can also help overcome resistance to change by shifting around managers with entrenched views.

There are limitations, however, to the use of political appointments. Although it might seem that appointing a larger number of officials to the bureaucracies will increase the White House’s control over their behavior, it can be difficult to find people who are loyal and ready to embrace change as well as qualified to implement change. Political campaigns attract loyal outside experts but do not ensure their competence as experts and government officials. Those who possess the expertise needed to understand, reform, and reorganize bureaucracies are more likely to hold views similar to those bureaucracies and hence be less suited to implementing changes, even when they are politically loyal to the president. Conversely, appointees who are loyal to the president and share the administration’s desire for change may be less likely to have the specialized knowledge and authority needed to be effective in pressing for bureaucratic change. Some appointees, meanwhile, are chosen for reasons other than their loyalty and competence in the job. Plum ambassadorial appointments, for example, are often a payback for large campaign donors. As a result, at least some political appointees will lack the policy knowledge, management, or persuasion skills required to change the bureaucracies to which they are assigned.

The second method is to empower the NSC staff to drive the change. Some presidents prefer to use the NSC in a coordinating role between the agencies, others as one of the main drivers of policy. A coordinating NSC may encourage continuity rather than change because the different bureaucracies it coordinates are unlikely to produce policies that push far beyond their existing capabilities, interests, and views. Therefore, an NSC empowered to direct foreign policy is often necessary for driving any significant change in direction.

Yet empowering the NSC to do more than coordinate policy poses institutional challenges. NSC staff can intimidate, cajole, and reward their counterparts in the different bureaucracies, but they lack direct authority over them. Deputy assistant secretaries, assistant secretaries, and undersecretaries take their orders from the cabinet officials at the top of their departments, not from the White House. And even skilled and experienced NSC staffers are likely to lack the technical expertise needed to convincingly translate White House aims into specific actions the bureaucracy must undertake. Alternatively, appointing to the NSC people who have the expertise needed to direct the bureaucracies means choosing staff that come from within the bureaucracy and thus share its values and culture to some degree. Empowering the NSC to take an activist role also tends to degrade the capacity of overburdened NSC staff for the strategic analysis needed for sound foreign policy.

The third solution is to persuade the bureaucracy of the need for change and to dedicate presidential and cabinet attention to the task. Presidents committed to change will have to use their political capital and powers of persuasion. The White House communications staff will be focused on selling any major change to the public and the congressional liaison staff will do the same for Congress, but presidential persuasion must also be directed at the bureaucracy. The White House needs to design an internal campaign aimed at convincing the civil service that the change is needed and nonthreatening, even if the effort cannot be expected to win over all the parts of a change-averse bureaucracy. It should also frame the change in terms of the losses that the status quo creates not only for the nation but also for the specific groups that must carry out the change. A sustained effort at communication—by the president and also the vice president, the national security adviser, and the secretaries of defense and state—in the form of speeches, memos, and visits to the departments will pay dividends in bringing about the new foreign policy. Ideally, this effort will identify internal influencers within the bureaucracy who can be won over to change.

Crucially, major foreign policy change will be much easier in periods of fiscal largesse. Fear of losing funding is a central motivator for bureaucracies and a key reason they resist change. When there is enough money to go around and fewer budgetary fights, they are less inclined to fear change and more inclined to embrace it. A corollary is that a change aimed at reducing foreign policy spending will be inherently more difficult to achieve than one that is spending-neutral or increases spending. This is an important conundrum for those who seek to reduce U.S. spending on foreign policy, whether on defense, diplomacy, or foreign aid.

What is more, bureaucracies are likely to change slowly, especially in the absence of a major crisis to spur them on. Pushing them too hard can be counterproductive. The culture of the government bureaucracy is deeply rooted and nearly impossible to overturn within the time frame even of a two-term presidency. The difficulty of changing organizational culture is one reason why experts advise companies against attempting far-reaching changes and instead recommend focusing on altering tasks and processes. There are always positive aspects of organizational culture, and holding these strengths up for praise while focusing on eliminating a few problematic aspects will have a higher chance of success.

Trying to circumvent the government bureaucracy by consolidating decisionmaking in a small group and acting in secrecy, as the Nixon White House did, can easily backfire.

Trying to circumvent the government bureaucracy by consolidating decisionmaking in a small group and acting in secrecy, as the Nixon White House did, can easily backfire. The Trump administration anticipated resistance from the bureaucracy but ended up generating or exacerbating it, sometimes by acting in secrecy and other times by acting too publicly, for example, by announcing policy via Twitter before consulting with the bureaucracies. The president placed tight groups of political appointees at the top of agencies like the State Department and DNI, who then insulated themselves from their organizations. By attempting to circumvent the bulk of the agencies that it needed to implement its foreign policy, the administration tended to increase the likelihood of the bureaucracy to work against it.

Firing bureaucrats in large numbers is also unlikely to work. There is no ready reservoir of competent civil servants to fill relatively low-paying jobs in the bureaucracy, especially if one of the main benefits of these positions—job security—is removed.

Congress’s Role in Change

Congress is often assumed to be impotent in performing its constitutional duties on foreign policy. By this logic, any effort to bring about strategic change might as well ignore the legislative branch. But this view is a partial truth at best. Discussions of strategy too often ignore Congress’s crucial role in strategic change. Congressional support was an important factor in overcoming bureaucratic objections to NATO enlargement, whereas congressional opposition amplified bureaucratic resistance in the case of Carter’s failed attempt to withdraw forces from South Korea.

Under the Constitution, Congress possesses extensive powers to make foreign policy, including the right to declare war, raise military forces, levy taxes, impose tariffs, appropriate funds, advise and consent on treaties, and confirm high-level appointments in the foreign policy bureaucracy. Yet by the 1970s many lamented the lack of power Congress exerted over the White House on foreign policy. The War Powers Act of 1973 was intended to limit to ninety days the executive’s use of military force without the authorization of the legislative branch, but Congress has yet to invoke it to get a significant ongoing military operation to stop. The presidency emerged even more dominant during the George W. Bush administration, when the executive branch claimed sweeping prerogatives and Congress diminished its own influence by swiftly authorizing an open-ended war on terror. Congress has still not revoked the war authorizations that it passed in 2001 and 2002.

Recent scholarship, however, sets out ways in which Congress sometimes has more influence on foreign policy than it appears. Legislators can and regularly do exert influence through indirect and direct means. When it comes to foreign policy, relations between Congress and the executive better resemble a tug-of-war than a one-way street.

Congressional power over foreign policy is most limited during a crisis, when the executive branch has the proverbial ball. This is particularly true in the early stages, when the White House has access to more intelligence and information and the ability to deploy forces into the field, thus changing the objective circumstances. At that point, fear of being charged with a lack of patriotism in a crisis encourages many members of Congress to hold back criticism and support the president.

Congress’s limited power during national security crises may help explain why its influence is sometimes thought to be so low. In a crisis, public attention is at its highest, events are dramatic, the focus is on the White House, and Congress is relegated to the sidelines. As the initial drama fades, however, Congress can become better-informed by holding hearings and examining intelligence. It can also evaluate the results to date of the president’s approach. Congressional leaders may then grow bolder and more willing to stand up to the president.

In recent years, Congress has asserted its influence through other methods besides providing advice and consent on treaties and exercising its constitutional authority to declare war. Instead, Congress may affect public opinion when leaders speak for or against specific elements of the administration’s foreign policy, as occurred with increases and decreases in troop levels during the Afghanistan and Iraq wars. Congress may also debate legislation that is critical of the administration’s policy or hold hearings aimed at pressuring the White House to change course. One should not exaggerate the impact of congressional hearings or of the statements of congressional leaders, but these actions make a difference by raising public awareness and increasing the political costs for the White House of persisting with an unpopular foreign policy.

Congress is in some ways more potent when the scale of policy change is large and U.S. ground troops are not in harm’s way. It can use the “power of the purse” and its statutory authority to change the structure of agencies and thus affect their absolute or relative power. For example, Congress could try to deemphasize the role of military force and strengthen diplomacy by increasing the State Department budget. Or it could seek to slow or even halt the growth in the defense budget in an effort to promote rationalization within the Defense Department or reduce its influence, as the Obama administration did with the policy of “sequestration.” Rebalancing spending away from defense and toward diplomacy has of course been hard to do, historically, even when supported by Pentagon leaders, but it is within the power of the legislative branch. When it comes to budgetary supplementals, such as the legislation that has been passed to assist Ukraine, Congress may be able to have a greater influence than in cases where budgets have been in place for many years.

Congress also can affect the policies and capabilities of the agencies by funding new programs within them, or it can even create, dismantle, or rearrange agencies. Congress has sometimes forced such rearrangements on the executive, as the Republican-controlled Congress did in the 1990s when it consolidated the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency and U.S. Information Agency into the State Department.

Although often seen as quiescent after 9/11, Congress was instrumental in designing and passing the legislation that turned counterterrorism into the focus of U.S. foreign policy. As noted, it passed two major authorizations for the use of military force that supported the Bush administration’s change in strategy, as well as key pieces of legislation that reshaped the national security bureaucracy, including the Patriot Act, the Homeland Security Act, and the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act. Congress also used its budgetary power to increase and reorient national security budgets toward the new global war on terrorism.

When Congress Is Likely to Support Change and When It Is Not

Congress has the capacity to promote strategic change yet often remains passive or obstructs change. Under what conditions might it choose to support strategic change, and under which conditions might it oppose change?

Congress contains many sources of resistance to change. There are bound to be a variety of different views in the 535-member body, and even within the two parties, but the tendency to support the status quo is usually strong. Human psychology resists change (see later discussion). Members of Congress have often made public commitments to uphold important aspects of the prevailing consensus, especially if they occupy positions that are important for change, such as seats on appropriations or other relevant committees. Changing their position opens them up to charges of inconsistency, at least absent a major crisis or an upheaval in public opinion. And even if members of Congress agree with the need for change, they may not care enough about foreign policy to spend precious political capital on it. Especially in the House of Representatives, whose members face reelection every two years, it may be too risky to spend political capital on anything other than domestic issues of importance to constituents.

Congressional resistance to change is bolstered by members who have self-interested political reasons for supporting the status quo, such as retaining military bases or weapons production plants in their district or state. The importance of the defense industry to some areas has created a constituency in Congress that has a major interest in maintaining specific weapons programs and high defense spending overall. Maintaining them can be of existential importance for these members, who will resist any change in foreign policy that requires a change in force structure and Pentagon acquisitions. By contrast, the cost of defense spending is spread across the entire nation. This diffuse interest does not strongly incentivize particular members of Congress to push for cuts.

Moreover, even when members believe change is needed, partisan political motivations may trump their personal views. Presidents seeking strategic change are unlikely to obtain cooperation from Congress when that body is controlled by the opposition party. They could attempt to overcome congressional opposition through a massive expenditure of political capital and disciplined prioritization of foreign policy over all other goals, but they are unlikely to try either of these routes unless the country is engaged in a politically salient war. By the same token, Congress is also unlikely to push a president toward an alternative foreign policy when the two branches of government are united under the same party’s control. Members do not wish to create political problems for the White House or fall out of favor within their party. Even when government is united, then, presidents need to spend time and political capital to convince Congress to support change, as their party is unlikely to offer unqualified backing.

Even when government is united, then, presidents need to spend time and political capital to convince Congress to support change, as their party is unlikely to offer unqualified backing.

Notwithstanding these sources of resistance, Congress can have a strong incentive to press for change when government is divided, especially when the majority party in Congress seeks change and the White House opposes it. In this scenario, Congress will be free to impose costs and constraints on the president. This began to happen when the Democrats took control of Congress in 2006 and agitated for changes in Bush’s approach to the war in Iraq, thus helping to sow the seeds of America’s eventual withdrawal. Forcing change on a reluctant president is difficult due to the challenge of collective action (especially given the limited salience of foreign policy), the intricacies of the legislative process, and the two-third majorities needed to overcome a presidential veto. Nevertheless, moments of disunity in government may offer opportunities for the promotion of new foreign policy ideas that challenge the status quo.

Public Opinion and Change

Public opinion sometimes plays a major role in strategic change. In the case of the Vietnam War, a swell of public outrage was a key factor in bringing about a U.S. withdrawal and other strategic adjustments. Similarly, in the case of 9/11, the public clamored for revenge against al-Qaeda. In such cases where public opinion is activated and cannot easily be quelled, change becomes almost inevitable. In other cases, however, public opinion is not a decisive factor. Ordinary Americans often have some interest in and knowledge of an issue, but their opinion proves malleable. For example, many Americans sought to contain defense spending after the Second World War, and the authors of NSC-68 were concerned that public sentiment might prevent Congress from approving higher levels of defense spending. However, the Truman administration successfully convinced the public that the global threat of communism required a major military buildup. Similarly, in the cases of NATO enlargement and Carter’s failed withdrawal from South Korea, Americans were largely uninterested, and the general public played little role.

Scholarship points to three main drivers of public opinion. The first is self-interest. The Rational-Activist Model holds that citizens form reasonable opinions based on their financial and other interests. This model assumes that citizens have the time and resources to follow politics, and that the media they consume is balanced and accurate.

The second driver is party affiliation. In the Political Parties Model, citizens take on the political views of the main groups with which they affiliate, and in the United States political parties provide the most relevant affiliations. Here citizens do not carefully form independent opinions but instead choose the party that better represents their views, and then they tend to absorb many of the opinions voiced by members of their party. Whereas the Rational-Activist Model places a high burden on citizens to take the time to form opinions on an array of issues, the Political Parties Model requires them only to choose their party affiliation.

The third driver is elite influence. Walter Lippman’s classic work Public Opinion contends that most Americans derive their political opinions from “what others have reported.” These “others” have a particular interest and expertise in the relevant area and communicate their views to the mass public. This group of experts is broadly defined as “political elites,” which include politicians, journalists, officials, activists, and specialists.

These three drivers of public opinion often overlap. For example, when citizens form an opinion after listening to a speech by a politician from the party they support, the Political Party Model and the Elite Influence Model operate simultaneously. A politician may also influence the opinion of citizens who support another political party, per the Rational-Activist Model and Elite Influence Model.

These models indicate the circumstances under which public opinion is likely to be most activated and become a major factor in strategic change. The Rational-Activist Model suggests that public opinion is activated when a particular policy has a direct effect on the self-interest of a large part of the public. This model helps to explain the permissive political environment after 9/11, when many Americans perceived global terrorism as a direct threat to their security and therefore supported a military response. The Truman administration offers another example of the relevance the Rational-Activist Model. Truman’s initial anxiety that a tax increase to fund NSC-68’s recommendations would activate U.S. public opinion against a military buildup indicated his awareness of the potency of self-interest as a driver of public opinion. His decision to conduct a campaign to convince Americans that Communism posed a real threat to their security also shows how elite messaging can influence public opinion.

Policies that do not directly affect large segments of the citizenry are less likely to activate public opinion. Most Americans have limited time for international politics, and the media focuses primarily on domestic politics and events. A foreign policy issue must break through the attention barrier in order to activate public opinion. This happens when there is partisan debate or when there is significant discussion in the media among political elites. In the cases of Carter’s intended withdrawal from South Korea and of Clinton’s enlargement of NATO, the issue never broke through the attention barrier.

Partisan issues can break through the attention barrier because they attract media attention and because staunchly partisan citizens are likely to follow what their party representatives say and do. Americans who strongly identify with a political party—liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans—are more likely to answer questions about foreign policy accurately. This finding suggests that partisanship can activate public opinion only among those Americans with a strong party affiliation. For instance, in the years following 9/11, some Democratic leaders cautioned against invading Iraq, thus activating the segment of the public with strong Democratic leanings, but not enough of the public to stop the 2003 invasion.

Debates among political elites—including journalists, activists, and specialists—can also activate public opinion on foreign policy issues as long as they play out in the open. Media plays a significant role in shaping public opinion when it covers these debates. Even when the media does not tell viewers exactly what to think, “it is stunningly successful in telling its readers what to think about.” For example, elite discussion in mass media played a key role in forming opposition to the Vietnam War. As Nixon put it, “The American news media had come to dominate domestic opinion about its purpose and conduct . . . In each night’s TV news and each morning’s paper the war was reported battle by battle . . . More than ever before, television showed the terrible human suffering and sacrifice of war.”

The Psychology of Change

Making major change in foreign policy requires many actors in the process to change a number of their beliefs. Strategic change often entails prioritizing some values over others, adopting new explanations for a problem, or even altering basic assumptions about how the world works. It means admitting at least some error. This makes change psychologically uncomfortable for many and extremely so for some. Like anyone else, policymakers and experts can go to great lengths to make facts conform to their theories about a problem, rather than adjusting these theories in the face of new evidence. Politics, careerism, and human sociability compound this psychological effect.

Politicians, for one, normally seek to be consistent over time in their policy commitments and views, lest they be accused of flip-flopping or not standing for anything. Political leaders can and do admit error, but doing so can be costly in a competitive political environment. Where there is partisan rancor over foreign policy, it is hard for politicians to change course because doing so will open them up to “I told you so” attacks from political opponents. This suggests that the partisanship that dominates American politics today will make it more difficult for individual presidents to change foreign policy than in previous eras.

Foreign policy experts also sometimes go to great lengths to avoid admitting mistakes for practical reasons, especially because doing so is almost never career-enhancing. Younger ones less committed to status quo views are potential advocates of change, but careerism can easily dampen their will to act as such if it means taking on powerful interests in Washington or abroad. Because the foreign policy elite is separated from other professional communities and relatively detached from interest group and party politics, its members are incentivized to maintain good relations with one another in order to retain employment as they move in and out of government.

This tendency toward stasis is compounded by human sociability, which in most foreign policy circles encourages conforming to the status quo.

This tendency toward stasis is compounded by human sociability, which in most foreign policy circles encourages conforming to the status quo. Conformism has upsides: foreign policy implementation is a complex, cooperative effort, and it would be disastrous if everyone attempted to pursue their own personal preferences. But a strong status quo bias from the desire for social acceptance is counterproductive in situations where there is a serious need for change. This may be one reason it took an outsider, Trump, to break the taboo on criticizing the U.S. effort to defeat the Taliban and rebuild Afghanistan.

For these reasons, if changing course requires facing up to past mistakes and overcoming a sense of lost time, resources, or personnel, then change is unlikely—at least as long as the people who made those mistakes remain in charge of policy. Overwhelming and credible evidence is needed to get those who are committed to an existing policy course to change their views, and mustering this evidence can take a long time.

The sunk-cost fallacy has been much studied in business. It is widely recognized that investors and managers have a strong, irrational tendency to stay the course once a particular investment of time, money, or effort has been made, even as losses mount. The problem gets worse as the magnitude of losses grows: the greater the sunk costs, the more effort people tend to put into defending the old course. In foreign policy, some scholars have used loss aversion to explain why the United States stayed the course in Vietnam even as the evidence of failure piled up.

This psychology appears to have been at play in the Defense Department’s handling of its training program for Afghan national security forces in the decade prior to the 2021 U.S. withdrawal. For years, the Pentagon insisted that it was making progress in training these forces, but those reports turned out to have been much exaggerated. The officers who wrote and approved them probably sought to ensure the programs could continue, lest the lack of progress come to light. The more money spent, the more it mattered that the program succeeded. No one at the Department of Defense set out to spend billions on an unsuccessful program, much less to dissimulate results from policymakers and the public. But once the sunk-cost fallacy set in, it became difficult to change course and tempting to exaggerate progress and minimize setbacks.

The upshot is that strategic change is more likely to be realized if framed as a way to prevent losses from the status quo than to reap gains from change.

The upshot is that strategic change is more likely to be realized if framed as a way to prevent losses from the status quo than to reap gains from change. A new strategy that offers the possibility of clear gains at the risk of clear losses is unlikely to convince policymakers to change their views and embrace it. But a novel approach that reduces the risk of losses, even if it also forecloses the opportunity for gains, may find a more receptive audience. Opponents of change, for their part, can succeed by focusing on the risk of losses, whether of security, power, wealth, or prestige. They can thereby block a proposed change, even one that is likely to bring about gains in those same areas.

How Powerful Is the President?

Many think of the president as enjoying far-reaching foreign policy and national security powers, a view popularized by Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., who coined the term “imperial presidency” in the 1970s. But recent scholarship paints a more complex picture of the powers of the president when it comes to foreign policy—one that many who have served in the executive may find closer to reality. Few would dispute that the president has far greater powers in acting “beyond the water’s edge” than domestically. But even in foreign policy, the White House operates under many legal, procedural, and especially political constraints. Congress, interest groups, the government bureaucracies, and the public can all influence policy and inhibit presidential ambitions. The right to direct the military might of the Pentagon makes presidents extremely powerful, but their latitude to use that military capacity (like any other capacity) remains circumscribed.

More important, the power of the president is considerably diminished when it comes to large-scale strategic change. It is one thing to be able to send forces into battle with the stroke of a pen, but it is another to alter the fundamental approach and posture of the United States in the world. The level of difficulty rises with the level of ambition; the larger the strategic change, the more the president’s constraints approach those in domestic policy. The long-standing idea that there are “two presidencies”—one for foreign policy and one for domestic policy—begins to break down.

More often than not, the White House wants to hold much of this political capital in reserve for domestic policy initiatives, and an incoming president’s foreign policy team is likely to discover that their ideas play second fiddle to domestic issues.

Every president comes into office with some amount of political capital, gained through the campaign, past experience, the support of key groups, and other factors. More often than not, the White House wants to hold much of this political capital in reserve for domestic policy initiatives, and an incoming president’s foreign policy team is likely to discover that their ideas play second fiddle to domestic issues. A crisis might help to focus attention on the shortcomings of the prevailing strategy, but even then, the president probably will not spend most of his or her political capital on foreign policy. Moreover, if the chances of successfully changing foreign policy are not high, the president may be unwilling to spend political capital in the first place, lest failure diminish his or her stature and make it more difficult to move forward on other fronts.

Moreover, modern presidents find the time for action to be quite limited. The clock starts ticking upon arrival in office, and most administrations feel they have very little time to accomplish many things. In their second year, the midterm elections loom, and a year beyond that the next presidential election campaign kicks off. While this can help focus minds on top priorities, foreign policy changes are rarely top priorities, and far-reaching strategic changes take time. The Biden administration’s withdrawal from Afghanistan was possible in part because it took place so early in the president’s term.

Major Change in Foreign Policy

If the foregoing lessons indicate anything, they indicate how difficult bringing about major changes in U.S. foreign policy can be. For example, successive administrations have struggled to shift foreign policy to focus on Asia, a shift that both Republican and Democratic administrations have now embraced for over a decade. A common explanation for the challenge in bringing this shift about is that enduring events around the world, especially conflicts in Europe and the Middle East, have prevented it. From this perspective, exogenous forces—for example, terrorists, failed states, Iran’s nuclear weapons program, or Russian aggression—have forced the United States to remain a globe-spanning military power. There is no question that the global environment inevitably shapes and constrains U.S. foreign policy and strategy, but this report shows these external effects do not tell the whole story. Overseas events are filtered through an extensive and complex system that governs the making of U.S. foreign policy and is intellectually, politically, and bureaucratically coded to respond robustly to crises in many parts of the world. That system is inherently resistant to change.

The Biden administration has consistently maintained that its priority lies in Asia and that China is the “pacing threat” of the U.S. military, yet it has expended massive political, financial, and military capital in supporting Ukraine and Israel in their respective conflicts. Clearly, events in both countries played an indispensable role, but so did the deeper institutional, ideational, and psychological forces described in this report.

In Europe, the calm Biden officials hoped for was shattered by an external crisis. Nevertheless, the administration’s response to that crisis has been to expand America’s security role in Europe and thereby create a new status quo in which the United States has a deep and costly commitment to Ukraine. The crisis itself was not of America’s making, and the Biden administration’s response to it was shaped by a complicated set of factors that include the president’s belief that the world is divided between autocracy and democracy and his desire to reassure European allies of the U.S. commitment to their security. But America’s strategy toward the war in Ukraine was also a consequence of forces that this report examines, including the cadre of Europe experts in Washington who have sought for decades to bring Ukraine into the West, strongly identify with America’s NATO allies, and resist changing NATO’s modus operandi, such as its open-door policy and its stated aspiration to admit Ukraine eventually.

In the Middle East, the administration successfully overcame internal and external resistance to ending U.S. involvement in the war in Afghanistan, but on other issues it has gone in the opposite direction from its initial intentions. An administration that once sought to right-size the U.S. role in the region is now proposing that the United States sign a binding security treaty with Saudi Arabia. As with Ukraine, the dynamics behind this policy are of course complex, but the policy reversal is strongly indicative of the inertial forces examined in this report.

An administration that once sought to right-size the U.S. role in the region is now proposing that the United States sign a binding security treaty with Saudi Arabia.

Over the course of the past twenty years, the United States has built up a very significant set of Middle East interests inside and outside the U.S. government, thanks in large part to the global war on terror. Middle East experts tend to view their region as integral to U.S. foreign policy. They naturally develop policy recommendations that assume or entrench the centrality of the region to broader U.S. strategy, and they often attribute immense value to America’s security partnerships in the region. The resulting inertial forces help explain the administration’s reluctance to draw down U.S. forces in Central Command aside from the withdrawal from Afghanistan, its deep commitment to aiding the Israeli government’s military response to the Hamas terrorist attacks on October 7, 2023, and its enthusiasm for a security treaty with Saudi Arabia. In contrast with the case of the war in Ukraine, in which moral and ideological factors explain a portion of U.S. policy, the Biden administration’s Middle East policy is best understood as a consequence of institutionalized bureaucratic, congressional, and public views on the region.

The factors examined in this report, therefore, play a role in explaining the difficulties that the administration has encountered in turning its focus to Asia. This is not to say that the Biden White House has accorded a low priority to Asia: to the contrary, the administration has worked energetically to bolster alliances and partnerships in the Indo-Pacific, win the U.S.-China technology competition, and since 2023 strengthen diplomatic contacts with Beijing. But U.S. resources, including the time and energy of the president and his most senior foreign policy officials, have often been diverted elsewhere. These diversions would have been greater were it not for the facts that there is bipartisan support for countering China in Congress and that the Department of Defense has now taken China to be its main adversary for nearly a decade.

The obstacles to change, and the challenge of overcoming them, were even clearer during the preceding four years under Trump. In his term, Trump sought to reduce the extent to which the United States underwrote European security and engaged in major military operations in the greater Middle East. On both counts, he encountered major resistance from the national security bureaucracy, Congress, and foreign policy elites.

Trump has promised to take a more aggressive approach if he is elected president in 2024. As media outlets and think tanks have highlighted, he might seek to replace large numbers of civil servants with party loyalists. As discussed above, however, this method has real limitations. The process of replacing large numbers of civil servants would not only take time and be messy but would also result in less effective bureaucracies. If a second Trump administration were to replace 500 mid-level intelligence managers with 500 mid-level managers from corporate America, U.S. intelligence collection and analysis would likely suffer for most of his term in office. Eventually, the replacements might learn their jobs. In the process, though, they might acquire some of the same views as their predecessors. In addition, the Trump administration could struggle to find senior and mid-level officials who share a commitment to change U.S. foreign policy in a particular way. Trump-aligned foreign policy experts are divided into several competing foreign policy camps, so even if his administration were able to find and install in government a large number of foreign policy officials who are loyal to the president and bureaucratically competent, they might not be able to adopt a coherent program of strategic change.

Ultimately, it may be that American strategy is influenced at least as much by domestic context as by the pressures of global context, especially the institutional, political, and intellectual forces that act on the foreign policy establishment. Only the most adamant devotee of the neorealist school of international relations would deny that domestic affairs influence foreign policy. But internal factors may be even more important than scholars have thought. Without major shocks to the system, external events are filtered through the existing strategic paradigm, one that several scholars of the post-Cold War period have called liberal hegemony or primacy, and through the political and bureaucratic institutions that have supported that paradigm. With planning, political will, the right conditions, and the right crisis, however, change is possible—even if it takes time.